| Our Monetary Mayhem Began With the Fed |

| Written by James Perloff |

| Thursday, 02 April 2009 18:00 |

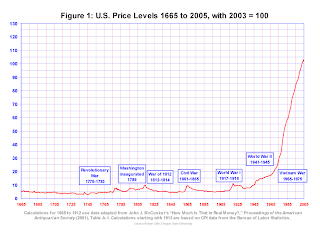

| Nearly all Americans know they are plagued by inflation. In 1962, a postage stamp cost four cents, a candy bar a nickel, a movie ticket 50 cents, and a pair of tennis shoes $5. A new imported Renault automobile cost $1,395, annual tuition at Harvard was $1,520, and the average cost of a new house $12,500. Over the last century, a dollar's purchasing power has declined over 95 percent — i.e., it won't buy what a nickel did in 1909. What causes inflation? The public hears various explanations from the establishment media — that oil's rising cost causes inflation, since nearly all industry sectors use it; or that inflation is the fault of American workers demanding wage increases, which has a ripple effect throughout the economy. In other words, Joe tells his employer, "Boss, my wife's expecting. How about a raise?" The boss says, "Joe, the only way I can afford that is by raising our prices — I'll have to pass the cost on to our customers." Then firms doing business with Joe's company say, "Since you've raised your prices, we'll have to raise ours." And so, all across America, prices rise because "greedy" Joe, and millions like him, asked for a raise. Furthermore, the public has been lulled into believing that inflation is inevitable, like "death and taxes." Indeed, based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the broad index used to measure the price of goods and services, that seems true. America has experienced general price increases every year since 1955, without exception. But as we can easily prove, inflation is not inevitable. Figure 1 depicts American price levels from 1665 to the present. Note there was no significant increase for the first 250 years. Little blips upward are on the graph, as during the American Revolution, War of 1812, and Civil War, when the United States issued large quantities of paper money to pay for those conflicts. Of course, increasing the supply of money (which is what inflation really is) diminishes its value, causing prices to rise. But notice that, after the wars, money always returned to its normal value. A dollar in 1900 was worth the same as in 1775; there had been no net increase in the cost of living since George Washington's day. Throughout this time, Americans asked for, and received, wage increases, without causing prices to rise overall. But look at the graph's right side. During World War I, our currency inflated, but instead of resuming its normal value afterwards, it continued inflating out of sight. American money, relatively stable for 250 years, began to rapidly and permanently lose its value. This did not happen by chance; every effect has a cause. Around the time of World War I, something significant must have happened to induce this transformation. As we shall see, the cause of this transformation has nothing to do with Joe and others who, suffering from the effects of inflation, asked for a raise. The Bankers' Beast The change came from a single factor: creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913. Though most Americans have heard of it, few know much about it. Ben Bernanke is current chairman of the Federal Reserve Board; Alan Greenspan held that position from 1987 to 2006. The Fed chairman has been called America's economic czar, because he and the board set U.S. interest rates. This in turn impacts the stock market's direction. If interest rates rise, CDs and other interest-bearing securities appear more profitable, causing money to flow out of the riskier stock market. But if interest rates fall, investors tend to return to stocks (the recent meltdown notwithstanding). Mutual fund managers try to stay ahead of the curve; when the Fed chairman holds a news conference, their fingers are often poised over their "buy" and "sell" buttons, hoping the chairman will reveal some hint about the direction of interest rates. The Fed was established when Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. But the original legislation, containing the essential points of that act, was introduced by Senator Nelson Aldrich, front man for the banking community. Few today have heard of Aldrich, but many are familiar with billionaire Nelson Rockefeller, who was Gerald Ford's vice president, long New York's governor, and one of America's richest men. His full name: Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller — named for his grandfather, Nelson Aldrich. Aldrich's daughter married John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and his son Winthrop served as chairman of the Rockefellers' Chase National Bank. Long associated with America's richest family, when Nelson Aldrich spoke on Capitol Hill, insiders knew he was acting for the Rockefellers and their allies in high finance. The legislation he introduced in the Senate, which became the basis of the Federal Reserve System, was not written by him. It was crafted by several of the world's richest bankers, at a secret nine-day meeting in 1910, at a private club on Jekyll Island off the Georgia coast. This is well documented. The first reporter to break the Jekyll Island story was B.C. Forbes, founder of Forbes magazine. Many years ago, Citibank was called National City Bank, and was largely controlled by the Rockefellers. Its president, Frank Vanderlip, attended the Jekyll Island meeting and discussed it in The Saturday Evening Post 25 years later: There was an occasion near the close of 1910 when I was as secretive, indeed as furtive, as any conspirator.... I do not feel it is any exaggeration to speak of our secret expedition to Jekyll Island as the occasion of the actual conception of the Federal Reserve System.... We were told to leave our last names behind us. We were told further that we should avoid dining together on the night of our departure. We were instructed to come one at a time and as unobtrusively as possible to the terminal of the New Jersey littoral of the Hudson, where Senator Aldrich's private car would be in readiness, attached to the rear end of the train for the South. Once aboard the private car, we began to observe the taboo that had been fixed on last names.... Discovery, we knew, simply must not happen. If it were to be discovered that our particular group had got together and written a banking bill, that bill would have no chance whatever of passage by Congress. Attending this meeting were agents from the world's three greatest banking houses: those of John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan, and the Rothschilds. Together they represented an estimated 25 percent of the world's wealth. Acting for the Rockefellers were Senator Aldrich and Frank Vanderlip. Representing the Morgan interests were: Benjamin Strong, head of J.P. Morgan's Bankers Trust Company; Henry Davison, senior partner in J.P. Morgan & Co.; and Charles Norton, head of Morgan's First National Bank of New York. But the most important figure, credited with running the meeting, was Paul Warburg, who belonged to a prominent German banking family associated with the Rothschilds. The latter, the world's most powerful banking dynasty, had grown rich by establishing central banks that loaned money to European countries. Its patriarch, Amschel Mayer Rothschild, said: "Permit me to issue and control the money of a nation, and I care not who makes its laws."In 1902, Paul Warburg came to America, intending to establish a similar central bank in the United States. Shortly after immigrating, he became a partner in Kuhn, Loeb, & Co., the Rothschilds' powerful banking satellite in New York City. The Rothschilds had long been linked to America's two foremost banking families, the Rockefellers and Morgans. They had provided seed money for John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company, and had influenced the Bank of England to bail out J.P. Morgan with a low-interest loan of 800,000 pounds, when his firm was verging on collapse in 1857. The axis of Warburg/Rothschild, Morgan and Rockefeller, and their Wall Street confederates, became known as the "Money Trust." It worked in unison to force a central bank on America. In 1907, Morgan, who controlled numerous newspapers, began a false rumor concerning the insolvency of a rival bank, the Trust Company of America. The rumor led to a drastic run on the bank by depositors. This was part of the frenzy that historians call the Panic of 1907. Subsequently, Morgan's and Rockefeller's newspapers clamored for a central bank to prevent further crises; Senator Aldrich echoed the call in Congress; and Paul Warburg traveled the country lecturing on why the change was needed. All this materialized in the Federal Reserve, which ultimately resulted from the legislation, penned on Jekyll Island, that Senator Aldrich introduced. Partly because of the senator's well-known ties to Wall Street, Congress never passed the Aldrich Bill itself. But the bankers gained acceptance of a very similar act, the Glass-Owen Bill, much of which was copied word-for-word from the Aldrich Bill. On December 23, 1913, when Congress was eager to adjourn for Christmas, the Glass-Owen Bill passed, officially creating the Federal Reserve System. This name itself had been carefully chosen to deceive Americans. While "Federal" implied public control, it is in fact owned by private shareholders. "Reserve" suggested it would hold reserves to protect banks, but it has no hard assets — only bonds and other instruments of debt, and, as we will see, "fiat money," created from nothing. "System" implied its power would be diffuse (through 12 regional Federal Reserve banks), whereas actual power would be centralized in the Board and the New York Fed with its powerful Open Market Committee. Monetary Motives Why did the bankers want the Fed? Whom do you suppose President Woodrow Wilson named first vice chairman of the Federal Reserve Board (a position from which national interest rates would be set)? Paul Warburg. Who was first head of New York Fed, the system's nucleus? Benjamin Strong. Thus the very men who had secretly planned the bank now controlled it. The foxes were running the henhouse. At the time, neither Congress nor the public had any inkling of the Jekyll Island meeting. Paul Warburg's annual salary at Kuhn, Loeb, & Co. had been $500,000, the equivalent of well over $10 million in today's dollars. He relinquished that for a Federal Reserve Board position that paid only $12,000. Was it altruistic patriotism that tempted Warburg to make this transition? Or was it because $500,000 paled in comparison to the countless millions he could make, for himself and his associates, by controlling American interest rates, and thus making the stock market rise or fall at will? Charles Lindbergh, Sr., father of the famous aviator, was a distinguished member of the U.S. House of Representatives. Congressman Lindbergh helped lead the fight against the Federal Reserve Act. In December 1913, he declared on the floor of the House: This act establishes the most gigantic trust on Earth. When the President signs this act the invisible government by the money power [Lindbergh here refers to the Rothschild-Rockefeller-Morgan alliance], proven to exist by the money trust investigation, will be legalized. The money power overawes the legislative and executive forces of the nation. I have seen these forces exerted during the different stages of this bill. From now on depressions will be scientifically created. The new law will create inflation whenever the trust wants inflation. If the trust can get a period of inflation, they figure they can unload stocks on the people at high prices during the excitement and then bring on a panic and buy them back at low prices. The people may not know it immediately, but the day of reckoning is only a few years removed. Lindbergh's words were prophetic. Did inflation follow the Fed's establishment? Yes; Figure 1 graphically proves the impact on price levels. Were stocks unloaded on the people at high prices, then bought back at low prices after a panic? Yes. The "day of reckoning" Lindbergh predicted came with "Black Thursday" and the Great Crash of 1929.The October 1929 stock market collapse wiped out millions of small investors, but not the Money Trust's insiders, who had already exited the market. Biographers attribute this to their fiscal "wisdom." But fiscal foreknowledge, especially of the Federal Reserve policy they were controlling, is more like it. The Fed increased the discount rate from 3.5 percent in January of that year to 6 percent in late August. While the Fed was not the only tool used to precipitate the crash, it was one of the most preeminent. Senator Robert Owen, who cosponsored the Glass-Owen Bill that created the Fed, later testified before the House Committee on Banking and Currency: The powerful money interests got control of the Federal Reserve Board through Mr. Paul Warburg, Mr. Albert Strauss, and Mr. Adolph C. Miller.... The same people, unrestrained in the stock market, expanding credit to a great excess between 1926 and 1929, raised the price of stocks to a fantastic point where they could not possibly earn dividends, and when the people realized this, they tried to get out, resulting in the Crash of October 24, 1929. Congressman Louis McFadden, chairman of the House Committee on Banking and Currency from 1920 to 1931, said of the crash: "It was not accidental. It was a carefully contrived occurrence. The international bankers sought to bring about a condition of despair here so that they might emerge as rulers of us all." McFadden stated further: "When the Federal Reserve Act was passed, the people of these United States did not perceive that a world banking system was being set up here — a superstate controlled by international bankers acting together for their own pleasure."Curtis Dall, son-in-law of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was the syndicate manager for Lehman Brothers. He was on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange on the day of the crash. He said of it: "Actually, it was the calculated 'shearing' of the public by the World Money powers." Afterwards, the Money Trust moved back into the market — exactly as Congressman Lindbergh had predicted. They bought up stocks that once sold for $10 per share at $1 per share, expanding their ownership of corporate America. Something From Nothing But stock market manipulation was not the only purpose behind the Federal Reserve. Another was creating money from nothing. The book that best explains this, and the Fed itself, is G. Edward Griffin's The Creature From Jekyll Island. As nearly everyone knows, the U.S. government is very expensive. The federal deficit for 2008 was $455 billion. This means that, on an average day, the government spent over $1 billion more than it took in. How does the government get money? Chiefly from taxes and the sale of government bonds. (The latter is a poor funding method, since money from bonds must be repaid later with interest.) But these revenues never come close to satisfying the federal budget's demands. Still, despite insufficient income, the government always meets its obligations. It continues to pay federal employees, defense contractors, Social Security and Medicare recipients, etc. How does the government manage this? It happens through a little-known mechanism. We'll borrow from an illustration given by Griffin. Let's say that, this week, the federal government is short one billion dollars needed to pay its employees. It sends a Treasury official to the Federal Reserve building, where a Fed officer literally writes out a check for $1 billion to the U.S. Treasury. This check, however, is not based on any assets the Fed actually holds. It is "fiat money," created from nothing. If an American citizen wrote a check without assets to back it up, he'd be jailed. But for the Federal Reserve, it's perfectly legal. The technical term the Fed uses for this is "monetizing the debt." Warburg and his accomplices knew that fiat money would give the government the potential to spend without limit. The banking cartel was, and still is, intimately linked to corporations that did business with the U.S. government. This meant these corporations (in modern culture, Halliburton, Bechtel, AT&T, etc.) could earn virtually unlimited revenues from government contracts. But the mechanism also benefited the bankers directly. As Griffin notes, what do you suppose the federal employees will do with that billion dollars in salary? Deposit it in their banks. How does a bank make profits? By loaning out deposited money. The more money in, the more it can loan. Thus, out of nothing, the Fed has created a billion loanable dollars for the banks. Furthermore, this billion automatically becomes ten billion, because under Federal Reserve rules, a bank need only keep 10 percent of deposits in reserve. For every dollar deposited, nine may be loaned. Thus the Fed's creation of $1 billion from nothing actually manufactures an additional $9 billion in loanable money for the banks. In Europe, the Rothschilds had perfected this system of fabricating bank deposits through central banks. Warburg largely designed the Federal Reserve from that model. For the bankers, the system meant countless profits, but for the rest of us, endless inflation. Why? Because every time the Fed creates dollars from nothing, it increases the amount of money in America, thereby decreasing money's value. A textbook example of inflation struck Germany in the early 1920s. Defeated in World War I, Germany was compelled to pay the Allies massive reparations. To meet this obligation, it printed huge quantities of money. This decreased the value of German currency so badly that by November 1923, a loaf of bread cost 80 billion marks. People carted paper money around in wheelbarrows; some used it as fuel for stoves. Whenever the Fed "monetizes" the debt, it does the same thing as Germany, only on a smaller scale. In today's high-tech world, of course, printing money is no longer necessary; the Fed can simply create money electronically, but the inflationary impact is the same. That is why, following 250 years of stable prices, we've had pernicious inflation since the Fed's birth in 1913. Incidentally, Washington politicians love this system. By letting the Fed finance their expenditures with money made from nothing, politicians know they can spend without raising taxes. Tax increases are a "kiss of death" at reelection time (as President George Bush, Sr. learned in 1992 after voters rejected him for breaking his pledge of "Read my lips, no new taxes"). When the Fed produces more currency, making prices rise, who do we blame? Not the Fed. Not politicians. Instead, we blame the local retail store. "Why are you guys jacking up your prices?" Or we blame the candy company for making smaller chocolate bars, or the cereal company for putting less corn flakes in the box. But these businesses are simply trying to cope with the same dilemma as we are: inflation. The culprit is the Federal Reserve, and the problem is not that prices are going up, but that money's value is going down. George Bush, Jr. waged war against Iraq without increasing taxes, and even introduced new tax credits and rebates. How did he manage this? Instead of raising taxes like his father, he had the Fed largely finance the war with fiat currency. This massive inflation caused the cost of food, energy, college tuition — everything — to soar. Actually, inflation is a tax, a hidden one the public generally doesn't perceive as such. A Well-coordinated Plot After developing this scheme, the bankers still faced a problem. The billions deposited in their banks, created from nothing, still belonged to depositors. To make it profitable, the bankers had to loan it to someone. They wanted to loan the money especially to one man: Uncle Sam — right back to the government through which they had it manufactured. Why? Because Uncle Sam would borrow astronomically more than individuals or businesses, and unlike the latter two, could always guarantee repayment. Government borrowing is generated through sale of bonds. The Federal Reserve was empowered to buy and sell U.S. government bonds. Who would purchase those securities from the Fed? To a great extent, the Money Trust's own banks and investment firms. We thus see yet another motive for the Fed: interest on government loans. But the Jekyll Island bankers still had a problem. How would America pay back all the interest on those loans? In 1913, the U.S. government had few revenue sources; its largest was tariffs collected on foreign imports. The bankers' solution? Income tax. Though now an accepted way of life, income tax was not always around. The original U.S. Constitution excluded it; in 1895, the Supreme Court ruled it would be unconstitutional. Therefore the only way the Money Trust could establish income tax was by legalizing it through a constitutional amendment. The senator who introduced that amendment in Congress? Nelson Aldrich - the same senator who introduced the incipient Federal Reserve legislation. Why did Americans accept income tax? Because it was originally only one percent of a person's income, for salaries under $20,000 (the equivalent of over $400,000 in today's dollars). On Capitol Hill, the tax's supporters issued assurances it would never go up. So patriotic Americans said: "If Uncle Sam needs one percent of my salary, and I can always keep the rest, it's OK by me!" But we all know what happened. Congress later dolefully informed Americans it needed to raise taxes a smidge. A few smidges later and, depending on bracket, we're losing 15 to 33 percent of our income to federal tax. It was a long-range plan. Some may object that rich bankers would never have wanted an income tax. After all, it supposedly "soaks the rich": the wealthier you are, the more you pay. It's true that the income tax structure is graduated. If an American today earns $100,000 or $200,000 per year, he or she usually owes lots of tax. But not the super-rich. The Warburg-Rockefeller-Morgan axis had no intention of paying income tax. When Nelson Rockefeller sought to become Gerald Ford's vice president, he had to disclose his tax returns. These revealed that in 1970, the billionaire hadn't paid one cent of income tax. Likewise, the Senate's Pecora Hearings of 1933 discovered that J.P. Morgan had not paid any income tax in 1931 and 1932. How did the Money Trust escape taxes? Primarily by placing their assets in tax-free foundations. The Carnegie and Rockefeller foundations were already operational by the time income tax passed. Let's review the scenario. In 1913, the bankers created the Federal Reserve, which not only gave them control over interest rates and thus the stock market, but empowered them to create billions of dollars from nothing, which they would then loan back to America. Also in 1913, the bankers installed the income tax, enabling them to exact repayment on these interest-bearing loans to the government. Only one thing was still missing: a significant reason for America to borrow. In 1914, just six months after the Federal Reserve Act passed, Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated, triggering the start of World War I. The United States participated; as a result, our national debt grew from a manageable $1 billion to $25 billion. Ever since, America has been immersed in skyrocketing debt — now officially over $10 trillion. The consolidation of power in Washington has also grown immensely, much to the benefit of the political and financial elites who hold the reins of power. Both a central bank and an income tax — particularly a graduated income tax that largely consumes the wealth of the middle class in the name of taxing the wealthy — are powerful tools for bringing about this consolidation. In fact, this is why Karl Marx, in his Communist Manifesto, called for both in his 10-step plan for establishing a communist state. Step 2 was: "A heavy progressive or graduated income tax." Step 5 was: "Centralization of credit in the hands of the State, by means of a national bank with state capital and an exclusive monopoly." Thus, in 1913, the United States enacted two of Marx's conditions for a communist totalitarian state. The original Constitution excluded an income tax, which the Founding Fathers opposed. Concerning money, the Constitution declares (Article 1, Sec. 8): "Congress shall have the power to coin money and regulate the value thereof." The Federal Reserve Act transferred this authority from elected representatives to bankers. In America today, many young couples work hard. Commonly, both spouses hold jobs. A young man might say: "When my great-grandfather came to this country, he worked only one job, but he owned a house, had seven kids, and his wife never worked outside the home. But me and Mindy, we're working two jobs, we have only one kid, and can barely pay the rent. What are we doing wrong?" But it's hardly their fault. When great-grandpa came to America, he paid no income tax, and his dollar was stable; it didn't plummet in value every year as it does now. But you'll be glad to know the bankers are sorry about the trouble they've caused. They realize people can't make ends meet, and they've found a solution: multiple credit cards. Can't afford this month's groceries? Just swipe some plastic. Of course, they will charge double-digit interest on that. Thus the banking cartel created inflation and income tax, robbing us of our income; therefore we don't have enough to live on, forcing us to borrow from ... the banks. The solution to the Fed? Get rid of it! Graph Source: Robert Sahr, Oregon State University See also "Creating 'Wealth': the Fed Shows No Reserve." |

No comments:

Post a Comment